At 85, T. Boone Pickens has discovered a powerful source of energy: his own. He’s got a new love, a new natural gas empire and a continuing mission to change the world. All he needs now is time.

Aboard his Gulfstream G550, T. Boone Pickens — legendary trader, corporate raider, energy visionary and billion-dollar philanthropist — slides off his shoes and reaches down to grab his feet. He’s got a surprise in store. Pulling his legs up onto the thick leather seat, he tucks himself into lotus position, as if getting ready to meditate. It’s proof that he’s still got it: physical strength, stamina, ability. A future.

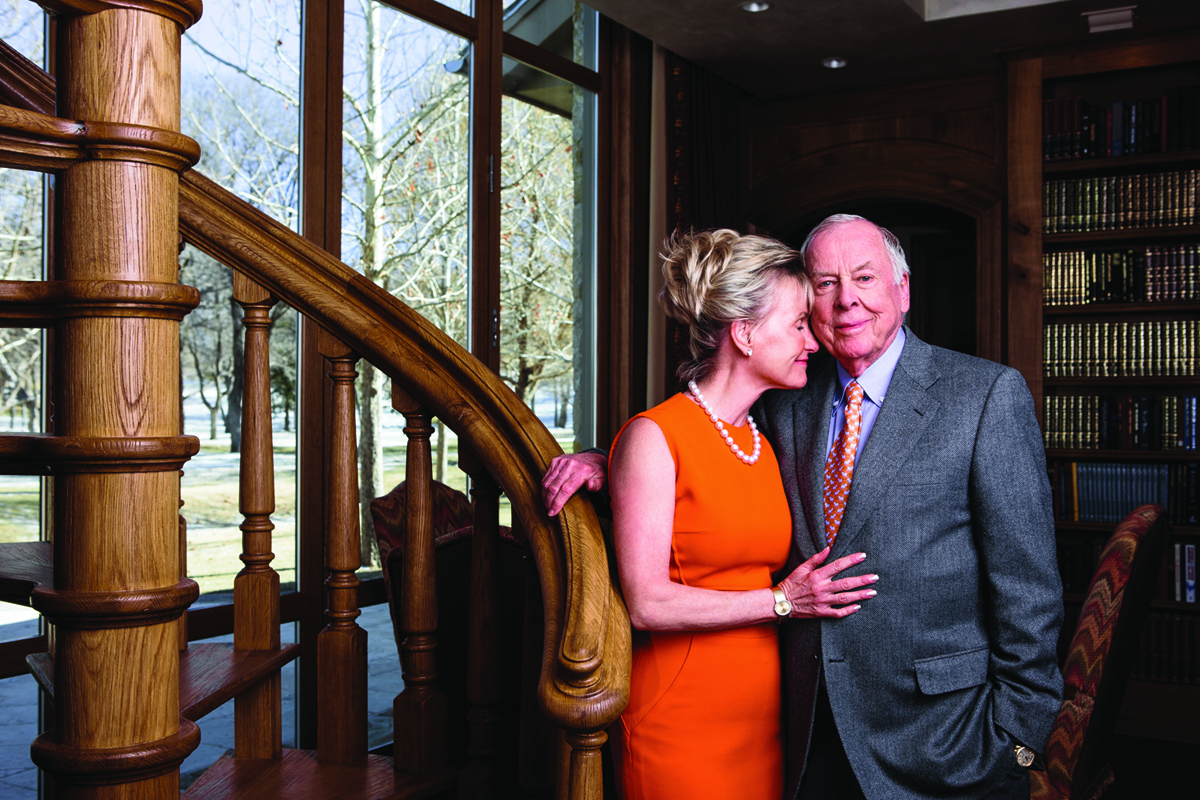

“He’s the most flexible man I’ve ever known,” Pickens’ wife, Toni Brinker, says with a wry smile. The two were married on Valentine’s Day in the lovely chapel next to the opulent lodge on his 68,000-acre ranch northeast of Amarillo in the Texas panhandle. It’s the fifth marriage for Pickens and the fourth for Brinker, who is some 20 years his junior. The two have known each other for a decade; Pickens was friends with her late husband, Norman Brinker, the restaurateur who founded the Chili’s chain. What sealed the deal for Pickens is that Toni enjoys traveling with him, is keenly engaged with the events of the day and always looks great everywhere she goes (especially with that enormous new diamond on her finger).

It was only two years ago that Pickens got divorced from his previous wife, Madeleine. And just a year ago that Pickens had “Toni” embroidered on the headrest of the seat next to his on his plane. (His own headrest features a TBP monogram.) Pickens’ beloved Papillon, Murdock, takes turns sitting in their laps. “If you can get your dog to like your girlfriend,” he says, “you’ll keep your girlfriend.”

Putting Toni’s name on the seat was another form of commitment for Pickens. After all, rather than settle in for a plush retirement, he lives on that Gulfstream, logging 500 hours a year jetting around the country to give speeches and interviews about the miracle of the American oil-and-gas boom, the importance of weaning the country from foreign oil and the no-brainer of powering cars and trucks with cheap natural gas instead of expensive gasoline and diesel. He’s the largest shareholder in publicly traded Clean Energy Fuels, which is building out a network of natural gas fueling stations. Retirement? “That’s not me,” Pickens says.

Pickens married Toni Brinker on Valentine’s Day. (Photo by Michael Thad Carter for Forbes, January 2014.)

Besides, he’s had too much fun reinventing himself over the years. In the 1980s, Pickens was the original corporate raider (“I prefer the term ‘shareholder activist,’” he says), famously going after the likes of Gulf Oil and Unocal. During the next decade, he lost control of his Mesa Petroleum by getting overleveraged in natural gas. By the 2000s, he reemerged as a hedge fund manager–and not only made his first billion after age 70 but turned it into $4 billion. Then in 2008, deep into his fifth decade of investing, he literally tilted at windmills, launching his ambitious Pickens Plan to build $2 billion worth of wind energy projects. The recession, paired with the shale drilling boom, gutted both energy prices and Pickens’ fortune. “My timing hasn’t been perfect,” he admits. “I’ve lost two billion, given away one and I’ve got one left.”

After he fell off The Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans last year, he tweeted to his more than 110,000 followers: “Don’t worry. At $950 million, I’m doing fine. Funny, my $1 billion charitable giving exceeds my net worth.” The quip was retweeted nearly 3,000 times.

“Some people are most brilliant when they don’t know what’s coming,” says longtime friend Jerry Jones, owner of the Dallas Cowboys. “Boone has as high a tolerance for ambiguity as anyone I’ve ever met.”

The reason is pretty simple, Pickens says. “I know I can make it all back–if I have enough time.”

At 85 , Boone Pickens knows he’s mortal. He figures he’s got another ten years left–if he’s lucky. A fitness fanatic since the 1970s, he’s also made damn sure that he’s going to be remembered long after he’s gone. The $1 billion he’s given away has gone to dozens of institutions. And he’s not exactly shy if they want to name a building after him. The biggest recipient of his largesse has been his alma mater, Oklahoma State University, where, in 1951, he earned his degree in geology. Among the $500 million he’s designated to OSU is $165 million for the athletics department. His name is now on the football stadium as well as the school of geology.

Pickens has also given more than $150 million to hospitals and medical centers, including $11 million to the University of Texas Center for Brain Health in 2006. After he made that gift, I convinced him that if he was going to donate so much money he should at least get his brain scanned. The subsequent MRI showed that part of the secret to Pickens’ success might be that his brain is about 30 years younger than he is. As he told me then: “I’d rather surround myself with sharp young minds than play golf and gin rummy all day.”

Pickens’ Mesa Vista Ranch is in the Texas Panhandle. (Photo by Thomas Roberts.)

Some of his donations are more personal than others. The day after he got an experimental eye injection at Johns Hopkins Medical Center in Baltimore to treat macular degeneration (which claimed his own father’s eyesight), the hospital held a lunch to honor Pickens’ $20 million bequest to the eye clinic. After doctors and administrators took turns saying nice things about him, Pickens told the audience: “My dad would say, ‘Where’d all these liars come from?’ My mom would say, “They shoulda gone on a little more.’” Then he added: “It’s fun to make it. It’s almost as much fun to give it away.”

To arrest the progress of the condition, Pickens flies to Johns Hopkins once a month for an experimental treatment that involves injections into the center of his eyeball. Has he gotten used to it? “Well, what if I kick you in the shins today and then do it again a month from now. Do you think you’d have gotten used to it?” But the treatment appears to be helping. His doctor, Neil Bressler, believes “this could cure macular degeneration.”

Whatever pain Pickens endures to preserve his vision is nothing compared to what he felt in January 2013, when his 21-year-old grandson Ty died from an overdose of heroin and Xanax that were provided to him by a college drug dealer. At Ty’s burial, out on his ranch, Pickens was more depressed than any time since he gave up liquor in 2000. “I almost had a drink of Scotch when I lost my grandson,” he admits. “Almost.”

He says that if there is any “silver lining” at all in Ty’s death, it’s that it unified his 11 grandchildren into a kind of generational coalition, determined not to let such a thing happen again. “He really did bring them all together,” Pickens says.

Out on his Mesa Vista ranch, Pickens proved how good his eyesight still is by driving his Cadillac Escalade at high speed over winding gravel roads. “You scared?” he asks. “I’m not blind yet.”

We stop for a tour of the modest house he grew up in — relocated from Holdenville, Oklahoma, 300 miles away. Bringing it to the ranch and restoring it was the idea of Pickens’ previous wife. They even transplanted old chunks of sidewalk with young Boone’s hand- and footprints from 1939.

“Ask him where he hid the money,” says Pickens’ handler, Jay Rosser, as we walk around. Pickens then shows me a spot in his bedroom closet where he had stashed $286 from his paper route under the floorboards–until, when he was 13, his mom made him take it to the bank. “I’ve always loved making money,” he says. “And since that first paper route, I’ve never been broke.”

Not that Pickens hasn’t had a few scares. “He’s a true role model for those of us entering the fourth quarter,” says Jerry Jones. “By the time you start the fourth quarter of a game, you’re banged up. Not pretty anymore. He entered his in one of the down times, in a serious depression. And he went from being broke to making several billion.”

Part of Pickens’ secret is that he tries not to look back too often. “I don’t dwell on the past,” he says. “I have too much to look forward to.”

In the office. With Murdock. (Photo by Michael Thad Carter for Forbes, January 2014)

Among the things Pickens looks forward to is a revolution in the use of natural gas to power cars and trucks. He aims to profit on it with Clean Energy Fuels. The nine-year-old publicly traded company has built the nation’s biggest network of stations to fill up cars and trucks with both compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Clean Energy boasts 200 locations across 43 states, many installed at Pilot/Flying J truck stops. It pumped the gasoline equivalent of 200 million gallons last year, filling up 26,000 vehicles per day.

The economics of natural gas fuel make total sense: For about $2.60 you can get the same amount of energy as you would from $4 of gasoline or diesel. Pickens became a proselytizer for natural gas vehicles (NGVs) more than 20 years ago, back when Mesa was one of the nation’s biggest independent gas producers, and he desperately needed to goose demand for the product. In 1997, he gave his close lieutenant Andrew Littlefair $3 million to launch what became Clean Energy Fuels.

The business is finally approaching critical mass. Today, 60% of the 8,000 new trash trucks sold each year are made to run on CNG, up from 3% in 2008. Pickens can almost taste the coming boom in NGVs now that heavy-duty truck makers like Navistar and Volvo are finally introducing big 13-liter and 14-liter LNG-fueled engines that are powerful enough to haul big trailers down the interstate. There’s no doubt in Pickens’ mind that the company is in a position to eventually make hefty profits. “I know I have to wait for the payoff there. But the gun is loaded and ready to go. All we’ve been waiting for is the 12-liter engine.”

Last October, I accompanied Pickens to the Securing America’s Future Energy conference in Washington, D.C. He spoke on a panel with General Motors’ then CEO Daniel Akerson and Waste Management CEO David Steiner. Akerson seized the occasion to announce the launch of a new Chevy Impala that can run on both CNG and gasoline. Steiner said that in four years Waste Management has transformed its fleet of 20,000 trash trucks from all-diesel to 80% natural gas. He said he has heard just one complaint about the CNG trucks: They’re so quiet that people can’t hear them coming down the street as a reminder to put the trash out.

Winter on the ranch (Photo by Michael Thad Carter for Forbes.)

Pickens was gleeful. Here, at last, was validation from some of the world’s most important companies of what he had been prophesying for years. Think what the long-term impact could be for America’s energy balance.

After the event in Washington and another eye treatment in Baltimore, the Boone Pickens air caravan headed to Pittsburgh. He had agreed to speak at a fundraiser for Stan Saylor, the Pennsylvania State House majority whip who is working to get more state funds to subsidize the purchase of natural gas vehicles, especially trucks.

As we sat in horrendous Pittsburgh traffic, Pickens spotted the Gulf Oil building that he used to visit during his raid on the company 30 years ago. The city has deteriorated since then, the steel mills rusted away. But Pittsburgh, he believes, could rise again thanks to the giant shale-gas field lying thousands of feet below.

“The Marcellus is probably the biggest gas field in the world,” Pickens told the small crowd at the fundraiser. “Your state was first in oil, in 1858 at Titusville. And coal, too. And now you have more natural gas than you can imagine.”

The challenge for Pittsburgh, Pickens said later on the plane: “You can’t get them to think big enough–they’ve been down too long.”

So what’s the secret? How can we all last as long as Boone Pickens? Back in Dallas, he challenges me to find out by working out with him. At 6 a.m., his driver picks me up. We head to his mansion in the posh Preston Hollow neighborhood. Through the darkened house and up the stairs is Pickens’ home gym. “It’s the cheapest insurance,” he says. Already at that hour Pickens has been on the phone to headquarters and has CNBC on the flat-screen. His personal trainer of 23 years is there too, checking his blood pressure as Pickens gets an early morning update from his traders on the phone. I do a triple take as CNBC puts Pickens’ face up on the screen and touts an interview with him that afternoon. After the trainer checks Pickens’ pulse rate, we get down to it: a mile on the treadmill. Fifty sit-ups. Two sets of 20 squats while wearing a 60-pound weight vest. A couple sets of 150-pound pull-downs. I manage to match him, but just barely.

Standing on the treadmill, Pickens looks over at me. “Is it clear to you yet that I’m trying to change the world?”

Yes, sir, it is. It sure is.