March 30, 3015

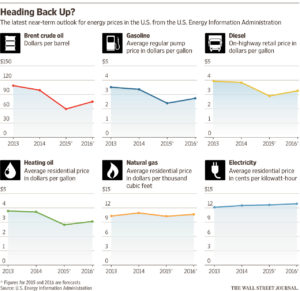

A few years ago, fears about declining reserves drove oil prices to new highs. Now, energy abundance is the operative phrase. Oil prices have tanked.

A few years ago, fears about declining reserves drove oil prices to new highs. Now, energy abundance is the operative phrase. Oil prices have tanked.

The Wall Street Journal’s Kimberley A. Strassel discussed how we got here, and where energy markets are headed, with Ted Nordhaus, chairman of the Breakthrough Institute, a think tank on energy, conservation and economic innovation; T. Boone Pickens, chairman of BP Capital Management; and Tom Werner, president, chief executive and chairman of SunPower Corp., a provider of solar-energy products and services. Edited excerpts follow.

How long will it last?

MS. STRASSEL: Are we in a new age of abundance of fossil fuels and cheaper energy prices?

MR. PICKENS: You know why you have $50 oil? Because the industry in the U.S. actually found too much oil.

MS. STRASSEL: How long do we think this cheap oil lasts?

MR. PICKENS: The rig count is extremely important. On Dec. 23, I said, “There are 1,509 rigs drilling in the U.S. for oil.” We have been up as high as 1,600, but with 1,509 you’re pretty well at the top for oil. Today, there are 822. We can’t replace our production with 822 rigs. You will go into decline probably in June. Then, oil will go back up. We’ll be at $70 a barrel by the end of 2015. By the end of 2016, you’ll be up to $90 to $100.

MR. NORDHAUS: I’ll leave it to Boone to tell us what oil prices are going to do in the next couple of years. But I think that when you really look at what’s happened with the oil markets recently, it’s a good illustration of what really changes everything is technology. We’re seeing huge economic geopolitical impacts, from fracking, a technology that’s really expanded the production frontier for oil. All technological revolutions do that in one way or another: They expand the production frontier.

We can put a price on carbon. We can regulate. We can do lots of other things around the margins. But things that are really game-changing are the underlying technologies that allow you to meet human needs without the same environmental impacts.

In the case of gas, it’s displacing coal, which is good. In the case of oil, it’s probably driving some increase in demand. But ultimately, that’s how you really sort of change the game. And that’ll be the case for the environment in the same way that fracking has changed our perspective on oil and oil markets.

MS. STRASSEL: A lot of renewable-energy stocks are trailing oil down in the stock market. Solar has stabilized a little bit. But can you compete?

MR. WERNER: The last time oil was at $50 was 10 years ago. Solar was five times as expensive then as it is now. It’s not the price of oil [causing this], it’s the pace of technology change.

Solar is going mainstream. Does that mean it’s the solution? No. Sun’s only out when it’s out, and you only produce electricity then. You need a reliable grid, probably need storage.

But is it the real deal? Is it economic? Absolutely.

Role of subsidies

MS. STRASSEL: Prices have come down. But renewables are also being integrated in states across the country because of renewable mandates, for instance. Now we’re seeing this trend, which is partly the reflection of energy prices falling, of states repealing those mandates. How does that affect you?

MR. WERNER: To put incentives in, they distort the market. Will my company make the best of it? Will we grow a business and get costs down and use scale? Absolutely.

MS. STRASSEL: You’d be happier if subsidies went away?

MR. WERNER: What I would say is we’ve got cost down. We did a $150 million project in Chile, no incentives, selling energy at market. Now, to be fair, it’s the best sun on the planet. But it’s commercially financed. So, commercially financed, merchant pricing, no incentives. It’s not theoretical. It is being done. That plant is online.

T. Boone Pickens says the political ramifications of cheap oil could mean the U.S. starts to export oil.

We’re publicly traded. It’s economically viable. So, we’re getting there. But is it there broadly? Is it the solution? No. It’s getting there. Certainly in southwest America, we have a lot of sun. We can compete. Absolutely. This is the real deal.

It’s also morphing. It’s not just going to be solar. You’re going to get energy management, combinations of energy management, solar and storage. And then you can do some really creative stuff on the electricity side.

MS. STRASSEL: How long before you become economic?

MR. WERNER: In my opinion, within five years. There’s enough demand that it’ll drive it. And when you can store energy that’s economic, that you can generate, that’s a game changer. That’s going to be really disruptive.

MS. STRASSEL: Ted Nordhaus, do you buy Tom’s argument?

MR. NORDHAUS: First, full disclosure, I have sun-power panels on my house. They’re great. They’re highly subsidized. I’m very happy that they are. It’s a fantastic deal for me.

But the most honest solar executive on the planet apparently is on stage with us. There’s sort of an irrational exuberance at times that takes over a lot of the discussion. It’s a great technology. It’s getting better. It has a really important role to play. And we’re not anywhere close to running the world on it.

There are a range of subsidies, and they are very, very substantial. My back-of-the-envelope calculations of my own system is about two-thirds of the cost is subsidized.

<a href=”http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-impact-of-cheap-oil-1427770862?tesla=y”>Read this article on wsj.com.</a>